Born on the Day of the Dead

When the color of your birthday is black

The Bible isn’t big on birthdays. It’s got bigger things on its mind, one might say, and also contains some choice examples of bad birthdays. In the Hebrew Bible, Pharoah (as told in Genesis 20) holds a lavish birthday party for himself, but one of the party favors is the execution of his chief baker, who was in prison with Joseph. (The chief butler, restored to his position, is more fortunate.) Better known is Herod’s birthday celebration (described in the Gospels of both Matthew and Mark), at which he foolishly promises Salome whatever she asks — a pretense which gives her mother, Herodias, the opportunity to have Herod execute John the Baptist. If this is where your birthday parties go, you can perhaps understand why Jehovah’s Witnesses eschew such celebrations.

The Jehovah’s Witness position is a minority one, however, and in Catholic countries, not only do you get your literal birthday, but also your “name day,” that is, the feast day of the saint after whom you are named. In Italian — I learned of this custom in Italy — this is called your onomastico, from the Ancient Greek word onomastikos (ὀνομαστικός), meaning “relating to naming.” And since there are many more saints than there are days in the year, there’s a day for all saints, All Saints Day, November 1.

Day(s) of the Dead

In a coincidence worth highlighting, Nov 1 is day one of a two-day Catholic holiday called the Day of the Dead, on which the living remember those departed. All Saints’ Day, which developed out of an original commemoration of Christian martyrs, is then followed by All Souls’ Day, in which the faithful departed (meaning, those not damned to Hell) were commemorated. FOOTNOTE: There is no All Damned Day, but an Irish tradition squeezes them in, on Oct 31 (All Hallow’s Eve).

November 2 was chosen in order that the memory of all the “holy spirits” both of the saints in Heaven and of the souls in purgatory should be celebrated on two successive days, and in this way to express the Christian belief in the “Communion of Saints.” Since the Feast of All Saints had already been celebrated on November 1 for centuries, the memory of the departed souls in purgatory was placed on the following day. (Weiser 309)

In contrast to the birthday-adjacent tradition of All Saints’ Day, All Souls’ Day is funereal.

The Office of the Dead is recited by priests and religious communities. In many places the graves in the cemeteries are blessed on the eve or in the morning of All Souls’ Day, and a solemn service is usually held in parish churches.

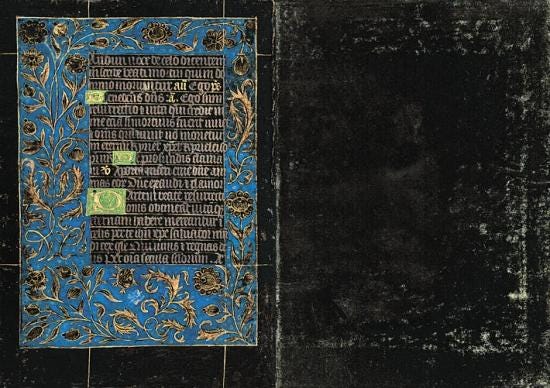

The liturgical color at all services on November 2 is black. The Masses are part of the group called “Requiem” Masses because they start with the words Requiem aeternam dona eis (Eternal rest grant unto them). The sequence sung at the solemn mass on All Souls’ Day… is the famous poem Dies Irae (Day of Wrath) written by a thirteenth-century Franciscan. (Weiser 310).

November 2 is my birthday. And so, every year, at church, my birthday is a funeral. FOOTNOTE: This is true under Novus Ordo, the so-called “ordinary rite”; under the rules of the “extraordinary rite” (namely, the pre-Vatican II Catholic tradition), All Souls’ Day would not be celebrated on a Sunday if it fell on one (but would be moved to Monday, November 3). Granted, it won’t fall on a Sunday each year; furthermore, since All Souls is actually not a Holy Day of Obligation, I could choose not to attend Mass. But obviously, since I’m always going to be aware of that date, it’s hard to avoid thinking of myself as born on the day of the dead.

Add a single hour

As a catechumen, one aspect of Catholic (or I suppose even Christian) belief that I’m avoiding thinking too much about — because it’s too much for me to get my head around — is this notion of eternal life. Jews don’t believe in heaven or hell, and I guess this worldview sits easy with me — at least in the sense that I’ve never felt the need to be good on earth because of post-death consequences. I was taught to be good (not saint-good, but good) because it was the right thing to do. Indeed, I’d go as far as to say that the focus on eternity was one of the least attractive things to me, overall, about Christian faith.

I’m opening up to it now, gradually; the key, I think, is the understanding that a believer’s relationship with God enjoys a fundamental characteristic of God, namely, his eternalness. From that perspective, the short span of a human lifespan — one bookended, ritualistically, by infant baptism and a funeral mass — is but a brief episode. You come in the doors of human community, and you go out of them again — both times in white and both times with water. You probably know that christening garments are white, but at a Catholic funeral, the coffin is draped in white and holy water is sprinkled on it, echoing infant baptism.

I happened upon a baptism the other day — the service begins outside the sanctuary, and it caught my ear that the priest mentioned not just the hopes for baby Josephine’s earthly life, but also her heavenly one. Talk about advance planning. But of course, in a different era, heaven might have been closer for many infants than we now take it to be; indeed, Louise Perry has surmised that one reason Christian belief used to be stronger was the comfort that eternal life gave to parents when their very young children died — a more common occurrence in centuries past.

That may be so, but such an attitude suggests a presentism of which we should be wary. Do we really think that our ancestors didn’t weep for their lost children because they were simpler people — whereas we know a cope when we see one? I think it is incorrect to place easy faith in the past, and empirical cynicism in the present; surely faith has been hard for some and easier for others, both then and now. What has definitely changed is not human nature, but rather what messages the mainstream culture sends. In our shared culture, these days, the afterlife, and more specifically, the Christian notion of salvation, is almost never mentioned. People may believe in eternal life, but the culture no longer does. We still live with death, but no longer do the dead and living live so closely as they once did.

If we are not so comfortable thinking about this connection between the dead and the living — which is what these first days of November, every year, are all about — perhaps we can approximate it by thinking about the connection between the present and the future? Our modern age of anxiety makes this much more familiar territory, for most people. For all that we may not worry about what happens after we die, almost all of us worry about what will happen next week. Jesus even connects these two preoccupations when he urges us to not worry because worry cannot actually extend our lives.

He said to his disciples, “Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat, or about your body, what you will wear. For life’s more than food, and the body more than clothing. Consider the ravens: they neither sow nor reap, they have neither storehouse nor barn, and yet God feeds them. Of how much more value you are than the birds! And can any of you by worrying add a single hour to your span of life? If then you are not able to do so small a thing as that, why do you worry about the rest? [...]” (Luke 12:22-26)

These comparisons — that scavengers are fed though they do not toil, and (later in this same passage) grasses can be beautiful despite their short lifespans — can only reassure us if we understand our destiny is that of eternal life, because we are of “much more value” (12:24) than plants or the lower animals. But instead — we of little faith! — worry about our earthly lives, even though we are unable to either know or extend their length. Our preoccupation with the life of bread and clothing thus separates us from the dead, because they no longer share such concerns. It is only once you believe that the dead are — as you will be — still living (in Christ) that a holiday of thinking about and praying for the dead makes genuine sense. You remember, yes, but you also anticipate. From this perspective, each birthday is not bringing you closer to death, but closer to life. After all, what’s another year compared to eternity?

Let your yes be yes

As the story of Herod exemplifies, the warning is not actually about birthdays, but about the fact that humans are obsessed with control. We swear, we promise, believing the best, but unable to see what we cannot see — namely, the future. Herod could not foresee that his promise to Salome would be used against his own desires. An even more famous example of an oath gone wrong is that of Jephthah, recounted in the second half of Judges 11, who swears that he will offer for sacrifice — if God will return him safe and sound from his battle with the Ammonities — whatever should come first out of his house upon his return. Alas, that turns out to be his only daughter. She asks to be allowed to mourn her maidenhood for two months, and then submits to her father’s grisly promise. What was supposed to be thanks for preservation of life becomes the entire end of Jephthah’s line, for his daughter is (unusually) his only child.

Just as Jesus urges us not to worry, he warns us not to swear:

“Again, you have heard that it was said to those of ancient times, ‘You shall not swear falsely, but carry out the vows you have made to the Lord.’ But I say to you, Do not swear at all… Let your word be ‘Yes, Yes’ or ‘No, No’; anything more than this comes from the evil one. (Matthew 5:33-34;37)

We promise for the same reason we worry: we are concerned with our earthy futures, futures we believe we can control more fully than we can. The message of the Gospel, the good news, is that we can surrender that control to the Lord. We need not grasp at earthly things, or worry over earthly problems; we need only love the Lord with all our heart and our neighbor as ourselves.

Add a single hour

I live quite close to our parish, and so I can do things like stroll up to hear the Office of the Dead at 1:00 AM. This took place during an all-night Eucharistic vigil, Saturday through Sunday. Don’t mistake my curiosity for piety; since I’m new to all this, and since we live so close, I just want to take advantage and experience all these things that are new to me.

There were maybe eight people in the sanctuary, including the Dominican priest charged with leading the liturgy. We were gathered to be close to the multitudes of the departed, but my first thought was that we also used to be closer to one another: if a hundred or so people could have walked to church, perhaps such vigils would be more popular. But knowing how sleepy I felt, I wouldn’t want more people to be in their cars.

In the dim of that wee hour, one line stood right out for me — the takeaway that satisfied my curiosity. It was the antiphon to the first Psalm:

Come, let us worship the Lord, all things live for Him.

Like the Liturgy of the Hours in general, the Office of the Dead relies heavily on the Psalms. And this line itself is based on Psalm 95:6:

Come, let us bow down in worship,

let us kneel before the Lord our Maker;

That psalm continues with a familiar pastoral (literally) metaphor:

for he is our God

and we are the people of his pasture,

the flock under his care.

But all things live for Him? That’s a new way of putting it — it puts it not from our perspective, but from His. From his perspective, a living human and a once-living human share something: His image, his Maker’s mark. In no small way, for us who are still alive to pray for the dead, to live our brief lives in communion with them, is to look at our own lives from the perspective of the eternal.

The liturgy ended. I stayed for a few minutes longer, praying in the dim silence, before making my way home in the darkness. I saw a lone doe in an empty driveway. It’s that time of year — and that time of the night. I thought, I don’t even know what happens in my own neighborhood when I’m asleep — what do I know about the rest of the world, or the whole of history? In short, nothing. I felt my smallness, and I also felt something else: my belongingness in the bigness. Me, that doe — and every other living thing that neither she nor I can see or know — are connected. All things live for Him.

I stepped back inside my house. I took the bread I’d had proofing in the oven, shaped it, and set it in its banneton and placed it in the fridge. I put on my pajamas and brushed my teeth and crawled under the covers. After a while, when I looked at my phone, I saw that it was 1:18 AM — we had, in fact, added a single hour. Even though, of course, we had not.

And then I thought, that is exactly what eternity is like. From God’s perspective, the hour is spent, but then the hour is new again.

Happy birthday, I thought to myself, and I fell asleep.

Gustate et Videte | “Taste and See” (Ps. 34:8) explores our thoughts on modern Catholicism.