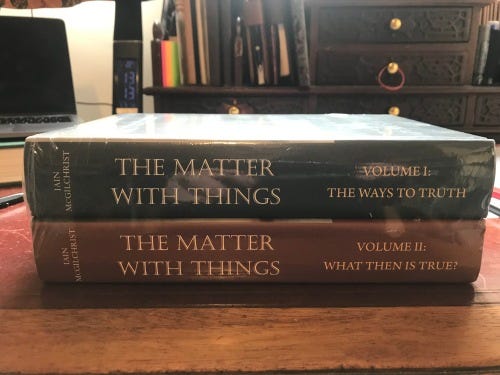

Although it is a dense 100 pages, “The sense of the sacred” is simply the last chapter of Iain McGilchrist’s two-volume, 1,375-page magnum opus, The Matter With Things (2021).

I read the entire thing this summer; Acton has read sections and had already read the author’s The Master and His Emissary (2009), which covers some of the same ground. But we agreed for the purposes of our discussion, we’d focus on this final chapter.

It is in this final chapter that McGilchrist fully considers what is at stake in a culture that no longer takes seriously the knowledge available to our right hemisphere. For it is this hemisphere, and this hemisphere only, that is able to perceive the greater mystery, ultimately ungraspable, but nevertheless in part accessible, about our world and our position in it as conscious animals.

And, in McGilchrist’s view, the consequences of ignoring this knowledge threatens our doom:

We are out of touch with reality, to which the right hemisphere’s world-picture would still give us access, if only we didn’t dismiss it. In our world, the real, possibly cataclysmic, threats we are facing are in effect denied, while in their place new, hitherto unimagined, ‘threats’ to our sensitive natures are invented, which then proceed to take up a disproportionate part of our attention. It puts me in mind of a patient I looked after who, following a right hemisphere stroke, was not the least bit concerned that the whole left side of her body was paralysed — indeed, like many right hemisphere-damaged patients, she denied that it was so; but she was absolutely convinced that she was being victimized by a patient in the next bed, who had, she thought, contrived to steal her magazines and subtly poison here food. (1313)

What does this have to do with God? Well, everything… but of course you have to understand what McG means by this term. If we accept that being is mysterious, and that our left hemisphere’s modality of asserting knowledge uses direct expression, which of course the mysterious by definition defies, then we need a term that, though it is specific, specifies that which cannot actually be specified.

What we need, in fact, is a word unlike any other, not defined in terms of anything else: a sort of un-word. This is no doubt why in every great tradition of thought — and perhaps beyond that, in every language of every people — there is such an un-word. It holds the place for a power that underwrites the existence of everything — the ground of Being; but, as I shall suggest, it holds a place for more than that, otherwise some such phrase as ‘ground of Being’ would itself be enough. To Heraclitus it was the logos; to Lao-Tzu the tao; to Confucius li, in Hinduism Brahman, and to the Vedic tradition rta; in Zen ri; to Arabic peoples, since pre-Islamic times, Allah; to the Hebrews YHWH. And in the Western tradition it is known as God. (1200)

Of course, once you have a word, you’re in the exact trouble you were trying to avoid — concretization of that which cannot be concretized.

It is inevitably a mendacious re-presentation of ultimate truth — that is to say, an idol. And the word God is obfuscated and overlaid with so many unhelpful accretions in the West that is not surprising that people recoil from this idol. It’s not just that, obviously, God is not some old man sitting on a cloud, but that very much else is often believed, or at any rate assumed by atheists to be believed by theists, badly gets in the way of an understanding. (1200)

McG is not trying to argue for the existence of God, or explain anything by invoking God, but rather to argue that “[t]he recognition of God is not an answer to a question: it is to fully understand the question” (1203).

Only in the last few years have I come to realize that it was this inquiry that drew me to the life of an intellectual, that attracted me to grad school in the hopes of becoming a professor. I believed in the life of the mind because I wanted not the certainty of fashionable platitudes but awe and wonder. Reading McGilchrist is a simultaneous experience of relief and regret; I am grateful for the fact that there are now serious books that consider God as more than just the man in the sky only simpletons believe in, but also sad that my own education lacked any of this material. Of course it did, though:

That awe and wonder are the end as well as the beginning of philosophy is one reason why God may be a better name than just ‘the ground of Being’ for this creative mystery. A phrase like ‘the ground of Being’, too, may have its conventional, cultural baggage — in this case, its presumed dullness. It could serve only as long as we see Being as having already something unfathomable about it — somewhat of the nature of God. But that is precisely what modern Western culture does not entertain. (1204)

It’s actually pretty amazing how the understanding of hemisphere difference can shed light on so many of our modern understandings about religion. Chief among these is the misunderstanding of belief, which, McG states, is “dispositional, not propositional.” This is not an understanding that satisfies the left hemisphere, and so follow the misunderstandings of not only militant atheism but also religious dogmatism. “Atheism and religious fundamentalism have a common quality that would be puzzling if we could not see that both stem from the same place in the brain” (1271). Another common pratfall among atheists is the idea that science and religion are incompatible. But this opposition is based on a left-hemisphere blindness to the greater context that it cannot perceive. “Belief is not part of a competition between differing reasons or explanations. God is rather seen as the ground of there being such things as reasons or explanations at all” (1273).

We are so habituated to the divide between science and religion that we lose sight of the actually important demarcation: a world where we let the ill-equipped left hemisphere rule our culture and one in which we let the right brain return to its proper role as master of the left, its emissary. You can be a left-brain-led atheist or a fundamentalist, just as you can be a scientist who understands the mysteries of the material world as processes, as prior relatedness. “Faith, like true science, is not static and certain, but a process of exploration that always has in sight enough of what it seeks to keep the seeker journeying onward” (1275).

It’ll be a stretch, but we’re going to do our best to do these dense pages justice in our discussion. If you can get your hands on a copy of this chapter, we promise it will be a rewarding read.

—George

Do your homework! And join us for the next conversation.