DYH! for episodes #010 and #011: D. H. Lawrence and Margaret Atwood

Novel thoughts on sex in a fallen world

Happy 2024! We’re kicking it off with something we’ve never done before on ReadFems: talking about fiction!

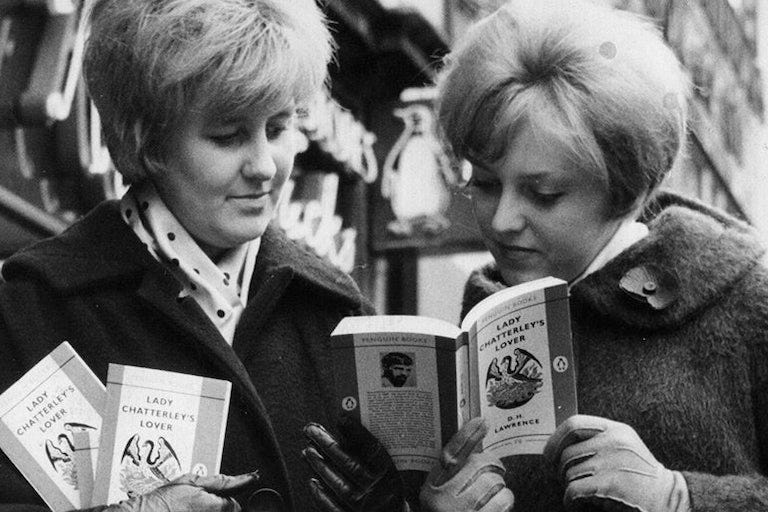

We’re pairing two novels that both describe worlds in which men and women are struggling to find a positive vision of the future: D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale.

It might seem logical for us to read Atwood, given how often we discuss women in society. Indeed, her dystopian classic (first published in 1985) has been rediscovered by a new generation of readers thanks to the Hulu series adaptation (which premiered April 2017). Atwood herself was then inspired to continue the story (also to be adapted for TV) with a new novel about Gilead, The Testaments (2019).

But why pair it with Lawrence’s infamously explicit novel about adulterous sex between a lady and a gamekeeper? Well, Acton ran across this article in First Things in which Patricia Snow reframes the novel1 as a cri de coeur for what Mary Harrington would call “rewilded” sex:

[I]t is necessary to distinguish the novel people imagine—a lusty, titillating tale—from the book Lawrence actually wrote…. What Lawrence was trying to recover were certain elemental realities, above all the primordial attraction… of a man for a woman, and a woman for a man, categories already under threat in a postwar world. It is this mystery of the other—the one specifically created for the human being from the beginning—that emerges unlooked-for in the Wragby forest…. In long, unhurried passages—the most beautiful passages in the book—Lawrence describes, from the point of view of the woman, and eventually of the man, the uneven, difficult emergence of a fully human relationship in a world also slowly returning to life, in a cold spring.

But even as the novel communicates certain elemental truths, it also gives the reader particular, prickly individuals, uncooperative individuals whose settled prejudices and painful pasts, private reservations and sudden, flaring resentments continually thwart the arc of conventional romance… In short, they are human beings, and when they finally come together in an act of physical intercourse, the sex that they have is not “hot” but eerily quiet, not enthusiastic but shot through with misgivings and fears. This is not casual sex. It is not entertainment or exercise, contracepted or masturbatory, looking out for its own pleasure above all. On the contrary, what the novel convincingly dramatizes is the terrifying seriousness of sex, the kind of sex that, when certain conditions obtain, can end in new life, but even when it doesn’t, knits a man and a woman together in a relationship unlike any other.

This is the kind of relationship that is under threat in the novel, as much in danger of extinction as any species in the natural world.

Acton and I believe that outside-the-box recuperations like Snow’s of Lady Chatterley’s Lover are exactly the kinds of explorations we should be undertaking if we want to restore social relationships to the primacy they deserve in our culture. We need to find ways to talk to one another in contexts where it is not possible to retreat to simple mottos — however dear they may be to us — but where we are required to look at the great variety of human personalities, conditions, and responses, and think deeply about them, embracing all the contradictions that will inevitably emerge. A writer like Lawrence can give us such a context, provided we do not reduce his novel to peddling smut on the one hand or a man telling women what women should want on the other (and yes, those are accurate representations of “conservative” and “feminist” critiques).

Academia has been reducing literature in this way for a long time; now, though, this mechanism has spread, and we are reducing ourselves and one another to atomized individuals and polarized political tribes. And we are increasingly miserable as a result. If we really want to live in a world built on relationships — those difficult, necessary, rewarding and good connections — we can no longer afford to think in the narrow boxes that put Matt Walsh on one side and Shout Your Abortion on the other. We need to take a fresh look at what we think we believe. This is why, frankly, we started this podcast; if George can read Mere Christianity, Acton can read Lady Chatterly’s Lover. We can learn both with and from one another, and the first thing we learn is that what we’ve been told — whether about our side or the other — is usually wrong.

Here’s to a year of plentiful (re)discovery and fruitful collaboration!

Do your homework!

— George

You can now listen to these episodes:

Snow mentions at the beginning of the piece that several years ago she’d read — in the same journal, no less — “an article withering in its condemnation” of the novel. It isn’t linked in the text, but a quotation assures me that she means this piece. It’s worth a read, too, for context. For starters, it goes a long way toward why I (George) was so floored by Snow’s piece.